Cooking with the Time & Talents Club Book

by Meher Mirza

The smell of dried Bombay duck infiltrates the air.

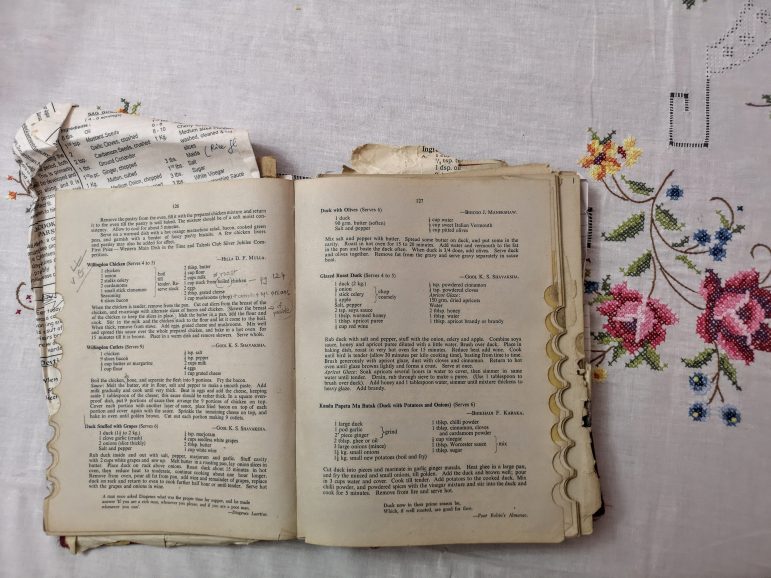

Mum is making the Parsi dish Tarapori Patio, a ruddy pickle made from the quintessentially Bombay fish, the curiously-named Bombay duck, assertively spiced and humming with the tang of vinegar. An old cookbook lies next to her, the pages brittle, dog-eared, covered with scrawls—“Add chopped coriander, 1/2 cup”; “easy for tiffin.”1

This kitchen treasure is Recipes from the Time & Talents Club, an iconic Parsi cookbook passed down from generation to generation. Mum’s came to her as a Christmas gift in 1975 through a dear old friend, her elderly piano teacher. There is an inscription within, scribbled in auspicious red—“Music has made my contact with you, but maybe cooking could become more important in the future. So here’s wishing you all the best for a bright and happy future. With love, Vera Aunty.”

Vera Aunty’s gift was the springboard from which my mum’s cooking took off. “Of course, I consult many Parsi cookbooks,” Mum says huffily, then relents to add, “but this one is for the ages.”

The history of Parsi food traces back to the Muslim conquest of Persia in the mid-7th century C.E. and the subsequent pressure, violent and otherwise, on the native population to convert from Zoroastrianism to Islam. A small number of Iranians fled, finding refuge across the Arabian Sea on the western coast of India, the modern-day state of Gujarat. From there, this Iranian diaspora seeped across India, enriching their adopted homeland’s cultural and economic landscape. Never a community of overwhelming numbers, there are less than 70,000 of us today and most live in Mumbai.2

Parsi food, therefore, is matted with influences, from the flavors of pre-Muslim Iran (a predilection for dried fruits and nuts, rose water, pomegranate, saffron, and a love of sweet-sour meat dishes) to British and Dutch cooking (thanks to their various imperial presences in western India) to the indigenous cuisine of Gujarat.

And when it comes to Parsi food, there was no greater influence than that of the Time & Talents Club. The Club, started by Gool Shavaksha in 1934, was peopled by a clot of upper-crust women, mostly Parsi, who yearned to be socially responsible at a time when many women were strangled by a lack of agency. The Club provided them an imprimatur of respectability, and its proceeds were shared with the poor. Such charitable pursuits were considered appropriate for women from respectable families; no doubt the Club was considered a passing fancy by several men. Yet it endured and grew.3

Although it may not have had the heft of government cultural organizations, the Club was keen on boosting Mumbai’s cultural scene. In 1963 they opened and oversaw the Victory Stall near the Gateway of India, once a culinary landmark, feeding the citizenry with their beer-soaked Parsi lunches and donating the proceeds to the widows and orphans of Indian soldiers. Club members wrangled concerts for the Mumbai public with the Berlin Chamber Orchestra and the Warsaw National Philharmonic, and they trundled in the maestro Yehudi Menuhinas and the famed pianist Benno Moiseiwitsch to perform for city audiences. Perhaps the ladies’ greatest triumph came when they secured a performance by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (whose music director at the time was Zubin Mehta, a Parsi son of Bombay) at the grand Shanmukhananda Hall. (This was despite the orchestra’s complaints of cockroach-infiltrated hotel rooms and, more terrifyingly, a bomb threat, though the latter was resolved by a quick call by a member of the Time & Talents Club to the police commissioner.)4

Almost everyone I know is connected to the Club in some way. My pediatrician juggles saving the lives of sick children with managing the Club’s many events. My great-aunt was a lifelong member, despite her husband constantly teasing her that it was “The Only Time & No Talents Club.”

But the Club is most heavily stamped onto our community identity through its cookbook. My London-dwelling cousin uses it as a emergency plan for when homesickness strikes. My friend Dilnavaz Contractor built her Parsi food pop-up around the book, inscribing into it her own personal inflections along the way: “The recipe for Parsi vegetable stew is one I fall back on every time. It’s a crowd pleaser. The one I secretly love though is the kharia ma chora (goat trotters cooked with beans), although unfortunately, only Parsis seem to like this one.”

The first edition was put together in 1935, all the profits from which went to charity. It was a time when India was still struggling to throw off the British yoke; a time of unrest and revolution, but therefore also a time of cross-pollination. Eased in with typical Parsi dishes such as caramel custard, patra ni macchi (chutney fish swathed in banana leaves), and the offal dish bhujan (heart, kidneys, and liver), were such recipes as undhiyu (a Gujarati dish made of root vegetables) and the south Indian mulligatawny. If Bhicoo Manekshaw (who later became an iconic Parsi cookbook author and chef in her own right) sent in her recipe for the voluptuous Fish Roxanne (fish crisped on a pan, then served in a bath of melted butter, caviar and lime juice), and Pinky Gindraux proffered her Pork Chops in Mushroom Soup (requiring the chops to take a long soak in butter and mushroom soup); then Khatta Tyabji sent in her recipe for mutton biryani, while Mani Kumana volunteered her recipe for Hyderabadi corn salan.

As one traces the various publications of the Time & Talents Club, it becomes clear why Niloufer Ichaporia King, author of the recent Parsi cookbook My Bombay Kitchen, calls the Club’s cookbooks a “perfect window into Bombay’s changing food-of-everywhere culinary culture.”5 During World War II, the ladies published a booklet of anti-waste recipes, including one that transformed a beloved Parsi egg dish (akuri) into an eggless one made with rotis cooked in masala. When I sift through my mum’s 1975 edition, I find Parsi regulars such as chicken farcha, and colmino saas (prawn sauce), but I also find snows, soufflés, and chiffons. The book is also sprinkled with food-related limericks and witticisms of both Gujarati and English origins, such as one epigram clearly of its time: “A woman who cannot make soup should not be allowed to marry.”

As later versions unspooled through the years, I encounter the further waxing and waning of culinary fashions: fewer snows and soufflés, more microwave recipes. The regressive sayings were tactfully weeded out. In this way, the older Time & Talents cookbooks become capsules of a vanished past.

Some things remain the same, though. There are always helpful tips throughout. The cooking instructions are crisp, almost clipped. There is no pandering to modern proclivities, such as pictures of the recipes. Even the latest edition, duly updated for modern living, is an oddity in an age that prizes a completely different vocabulary of cooking—it has neither the aggrandizement of restaurant cooking nor the glossy, flattened photographs of Instagram. It is simply good home cooking, mother’s cooking, standing stolidly in its own lane.

The Time & Talents Club, Recipes (Mumbai: Bombay Chronicle Press), 1975.

Rashna Writer, “Parsi Identity,” Iran 27 (1989): 129–31; Sayeed Unisa, R.B. Bhagat, T.K. Roy, and R.B. Upadhyay, “Demographic Transition or Demographic Trepidation? The Case of Parsis in India,” Economic and Political Weekly 43 (Jan. 2008): 61–65; PTI, “Parsi population dips by 22 percent between 2001-2011,” The Hindu, July 26, 2016.

Anisha Rachel Oommen and Aysha Tanya, “This old Parsi cookbook is as singular as the community whose recipes it documents,” Scroll.in, June 13, 2018.

Vidya Prabhu, “Nostalgia Lane,” Indian Express, May 9, 2013.

Eggless Bhakra Gluten free and Vegan – Vegetarians rejoice! – ParsiCuisine.com

Nov 11, 2019, 11:33 am[…] Time and Talents club book. Not only is it made from an organic maize rava which is gluten free, vegan and no eggs. Vegetarians rejoice! I found the maize rava in an indian grocery store. Amazon has the one listed below. […]